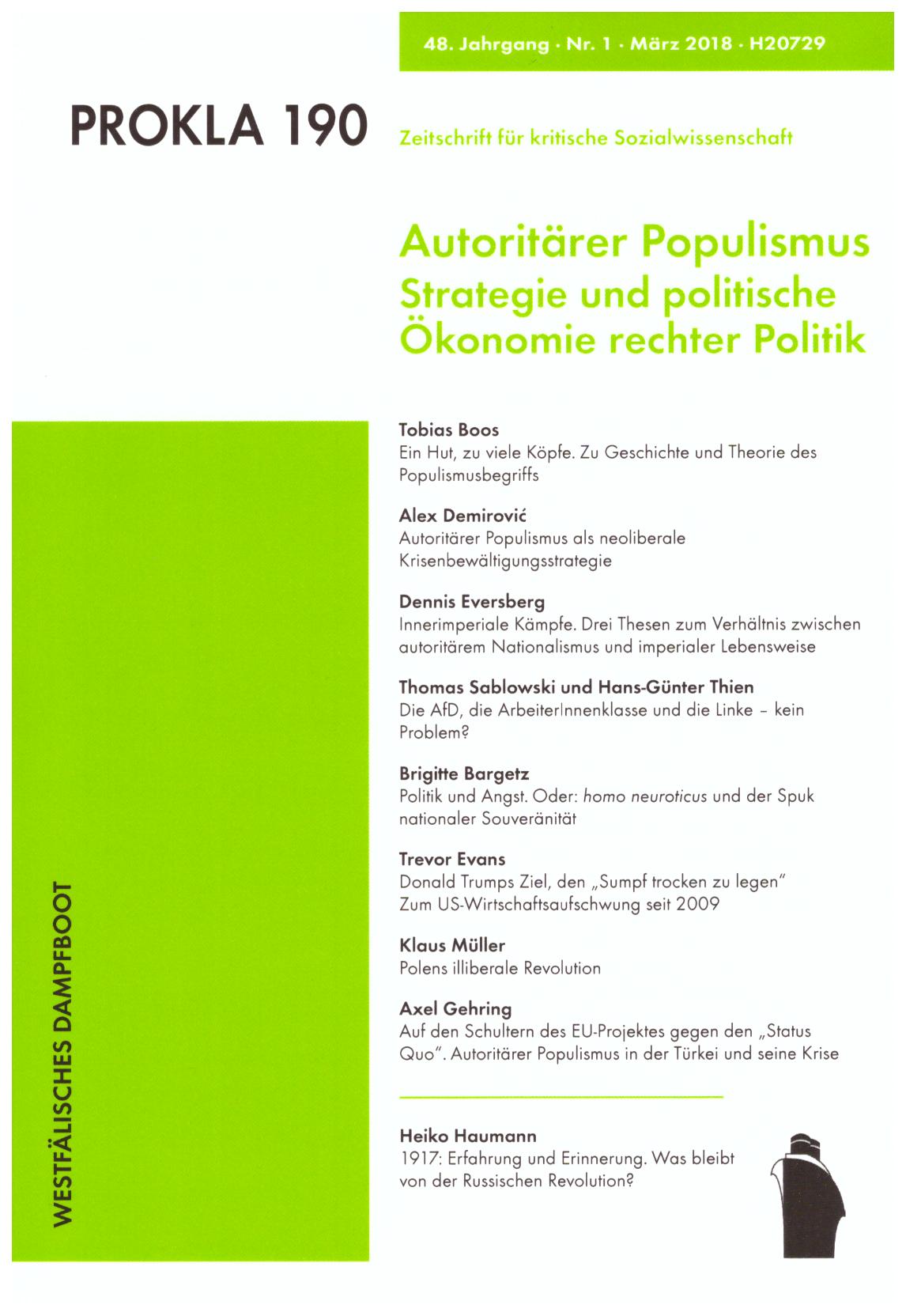

Editorial: Authoritarian Populism

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.32387/prokla.v48i190.28Keywords:

Editorial, right-wing-populismus, populism, AfD, Stuart HallAbstract

The present issue continues the research of issue 185 on the topic "state of emergency". In recent years, there have been numerous accelerated developments and political crises that have led to authoritarian government practices and contributed to a change in political forces. There is much to suggest that, in this context, the success of parties described as right-wing populist is more than just an expansion of the party spectrum and parliamentary space, but rather a new political regime. The rise of parties and politicians, which are characterized as "right-wing populist" in the prevailing discourse, has been a defining theme in recent years. The concept of right-wing populism refers to that of left-wing populism. Both terms are used pejoratively in the dominant discourse. Right-wing and left-wing populism are regarded as two variants of the same thing. This is based on a scheme that divides the political space into a positively connotated centre and two negatively connotated extremes: Right-wing and left-wing populism are, so to speak, regarded as softened forms of right-wing and left-wing extremism. In other words, right-wing and left-wing populism, according to the prevailing understanding, move precisely at the border between the centre (what is considered normal) and the extremes. They are treated according to the pattern of totalitarian theory. Yet the judgement on populism has already been established before its mode of operation has even been analysed (cf. D'Eramo 2013; Link 2017). From a critical, emancipatory point of view, the equation of right and left forces must be rejected. In addition, the question arises whether parties in which racist, sexist or fascist positions are represented are not played down by labelling them as right-wing populists. It is also distracted from the fact that, for example, the CDU or the BILD-Zeitung have also fallen back on ideological elements that are today classified as right-wing populism; the "bourgeois camp" or the "centre" are thereby exculpated. However, the concept of populism should not be given up hastily.

Downloads

References

D'Eramo, Marco (2017): They, The People. In: New Left Review, Nr. 103: 129-138.

Hall, Stuart (2014): Popular-demokratischer oder autoritärer Populismus. In: ebd.: Populismus, Hegemonie, Globalisierung. Ausgewählte Schriften. Bd. 5. Hamburg: 101-120.

Jun, Uwe (2011): Die Repräsentationslücke der Volksparteien: Erklärungsansätze für den Bedeutungsverlust und Gegenmaßnahmen. In: Linden, Markus (Hrsg.): Krise und Reform politischer Repräsentation. Baden-Baden: 94-123. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845231914-94

Link, Jürgen (2017): Populismus zwischen Normalisierung und Denormalisierung. In: kulturRRevolution, Nr. 72, Mai: 47-56.

Merkel, Wolfgang (2017): Kosmopolitismus versus Kommunitarismus: Ein neuer Konflikt in der Demokratie. In: Harfst, Philipp/ Kubbe, Ina/Poguntke, Thomas (Hrsg.): Parties, Governments and Elites. The Comparative Study of Democracy. Wiesbaden: 9-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-17446-0_2

Zürn, Michael/de Wilde, Pieter (2016): Debating globalization: cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as political ideologies in: Journal of Political Ideologies: 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2016.1207741